In May 2016, a survey on the world’s leading economies by the German NGO GfK Verein ranked Brazil (along with Spain and France) as the country where its citizens least trust their politicians. Like in the case of Spaniards, only 6 percent of Brazilians admitted to trust politicians. When asked specifically about mayors, a scarce 10 percent of Brazilians approved of their city’s leadership.

Over the past year, the corruption scandals in Brazil, brought to light through the “Lava-Jato” trials, have done little to improve this perception. On the contrary, approval of the country’s leadership is now at an all-time low.

Ex-ministers, ex-governors, ex-secretaries, former members of congress and entrepreneurs are now in prison facing long-term trials and penalties.

To give a simple example, five of the six members of the Rio de Janeiro Court of Accounts (responsible for overseeing state expenditures) were recently accused of–and arrested for–receiving bribes in exchange for tax breaks. An unprecedented event that left the state of Rio de Janeiro virtually without auditors, bringing the administrative machinery to a halt.

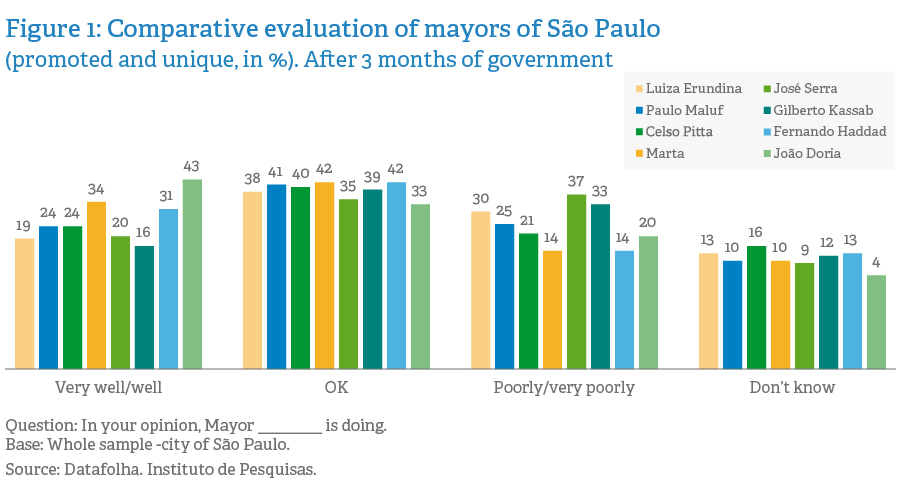

In a scenario such as this, how is it possible that João Doria, the mayor of the largest and most important city in Brazil, has managed to reach record popularity in little over 100 days after taking office, better than all his predecessors?

“43 percent of the people of Sao Paulo rank Doria’s management as good or very good–a first for any of the city’s mayors”

According to a survey by the newspaper Folha de São Paulo that evaluated the 100 days of the mayor’s term, 43 percent of the people of São Paulo rank Doria’s management as good or very good–a first for any of the city’s mayors.

This article is not an evaluation of Mayor João Doria’s management, nor the fulfillment of his Government Plan. It is a brief overview of some of the keys to how the current mayor of São Paulo has leveraged communication as a way to manage his reputation and maintain a direct dialogue with his people.

The politics of narrative beyond just messages

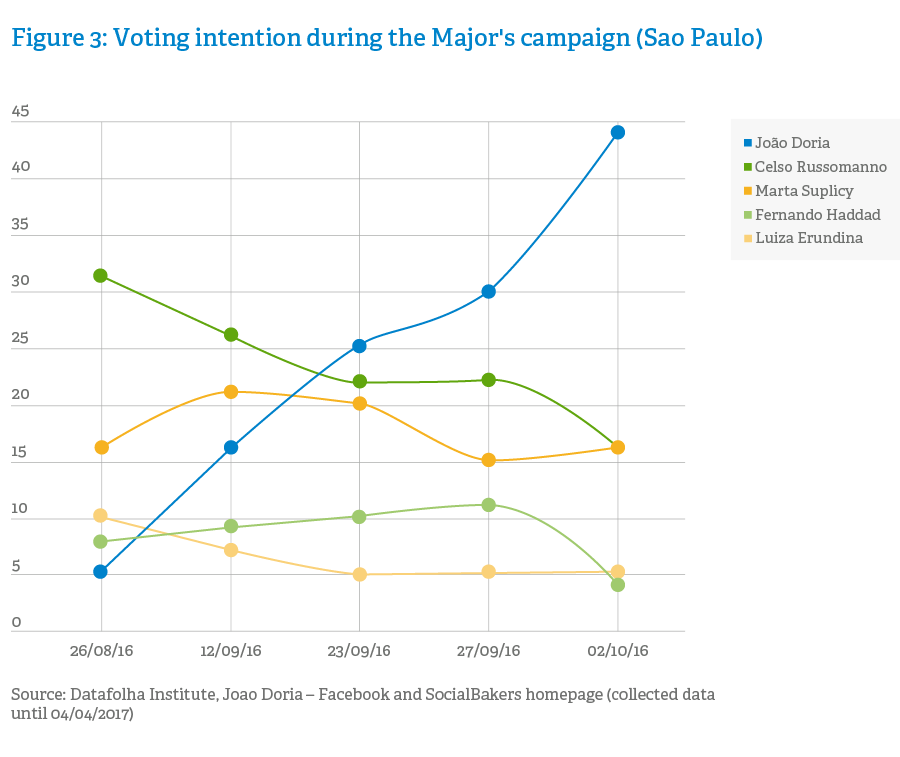

Against all odds, João Doria was elected mayor of São Paulo in the first round, with 53 percent of the votes. No poll had hinted at such a resounding victory.

His candidacy for mayor of São Paulo was Doria’s first time running in an election. A newcomer to politics, best known for his work as a journalist and as one of the city’s wealthiest entrepreneurs; Founder and President of Grupo Lide and specialized in high-level business networking.

Aside from the circumstantial (albeit no less important) issues of his rise to mayor, beyond beginner’s luck, two of the key factors of the process–which he has managed to maintain over his first 100 days in office–have been to present himself as a manager rather than a politician and to efficiently use communication to convey this narrative.

Like Barack Obama in the United States, Antanas Mockus’s first term as mayor of Bogotá, Justin Trudeau in Canada and José Mujica in Uruguay, Doria’s strength comes not from creating a key message (“I’m a manager and not a politician”) but rather from building and executing a government narrative around that concept.

And because this type of storytelling takes a massive amount of work to manage, communicating this narrative must be both effective and efficient.

The keys to storytelling

As Professor Fernando Schüler suggests, Doria has succeeded in “turning communication into a tool of governance”. This alone would suffice to account for much of his popularity. But how did he do it?

Defining the narrative’s main character

The character’s name is João Doria, a workaholic who only sleeps three hours a day and has a packed schedule that starts at seven in the morning. Nor does he rest on weekends, and he forces his team to keep up the same pace. He hates long meetings and established fines for secretaries who arrived late to scheduled meetings.

Unlike other mayors, Doria spends most of his time outside the office: a surprise visit to a hospital, cleaning a street dressed as a city cleaner, or using a wheelchair to demonstrate the inaccessibility of train platforms. He has also painted city walls gray in a crusade against graffiti and took a bus ride just like millions of São Paulo’s workers do every day.

In this narrative, this Mayor is the hero built in opposition to his predecessors, the bureaucracy and all that represents inefficient city management (the villains). It is in this way that the Mayor generates empathy with his target audience (Brazil as a whole?) and creates an emotional bond with them (positive or negative).

Mayor Doria has personified people that coexist in the day-to-day life of the city; not a character who kisses children or cuts ribbons, but rather one that stars in roles that require management and action.

In one of his first decisions as mayor, Doria declared war on the city’s graffiti, painting the walls of major avenues gray and erasing urban art works by artists of the sort of Os Gemeos.

In a recent interview, the mayor admitted to failing to separate artistic graffiti from urban vandalism, regretting the measure, thus adding an additional element to his character: humanity. A mayor who is wrong and says that he is?

Turning details into stories

Stories that become part of narratives are crucial for keeping the audience’s attention. Many times these stories are generated from small details. The following two examples should suffice:

The first refers to the published policy in which the mayor decreed an end to the formal treatment of city employees. Terms like “most excellent” will no longer be used, only terms such as Mr. and Mrs. “Call me simply mayor or João the Worker”, announced Doria on his Facebook page.

A model that, incidentally, Doria decided to follow after witnessing the informal treatment used at the office of mayor Horacio Larreta (another businessman-cum-politician) in Buenos Aires.

The second example was the suspension of the city’s Official Gazette. Printing the gazette was a minimum expense within the city’s entire budget. However, in times of crisis, these details turn into stories that shape the public opinion, in the same way that Doria did by selling the mayor’s official cars and cutting costs.

One of the hardest things to do in any narrative is to keep the audience’s attention over time. The use of details, as sources of constant stories, help maintain this tension.

Creating scenarios that the public can relate to

Another important element in good storytelling is to get the audience to relate to plot points and scenarios.

One of the pledges of Doria’s government has been the need to generate more agreements with private companies. This is not a new idea and it obviously refers to scenarios like privatization.

Not that this is not one of the objectives of Doria’s Government Plan, but it certainly is a facet that generates public tensions.

“Another important element in good storytelling is to get the audience to relate to plot points and scenarios”

Thus, the Mayor’s storytelling refers first to generating an emotional connection with the public. An example of this is the agreement Doria’s government signed with McDonald’s to employ the homeless. The pilot project contemplates a 40-hour emotional training course in order to rebuild the self-esteem and confidence of people who live on the streets of São Paulo.

Private initiatives are integrated into city management by including them in scenarios that citizens can relate to. According to the mayor, over five thousand jobs have been generated with similar initiatives, turning this into one of the most visible stories of Doria’s project with a huge media and social media impact.

Appealing to humor

At the end of March, Amazon launched a video ad campaign for its Kindle reader which showed fragments of stories projected on the gray walls painted by Doria in his “war” against graffiti artists. “We covered the gray with stories”, the video said at the end.

Doria–in a humorous response that imitated the ad’s video format (released on social media)–recorded a video with a message for the American company, which he posted on his social media accounts. “If Amazon has such love for São Paulo and for Brazil, then help our city by donating what the population needs and make it a happier city”.

Two companies immediately responded. Saraiva, an important chain of bookstores in Brazil, took to social media to express its interest in joint projects. Kabum, an online electronics store, also announced that it would donate computers and tablets to the city. Amazon wasn’t far behind and also announced on its Facebook page that it would donate Kindle readers and free books to schools.

Through humor and social media, the people of São Paolo saw how their mayor turned around a campaign that was a clear criticism of his policies.

(Last but not least) using transmedia storytelling and interaction

Many of these stories and details would not be as well-known were not woven into the social media strategy that made it possible for the mayor to reach more people using different formats.

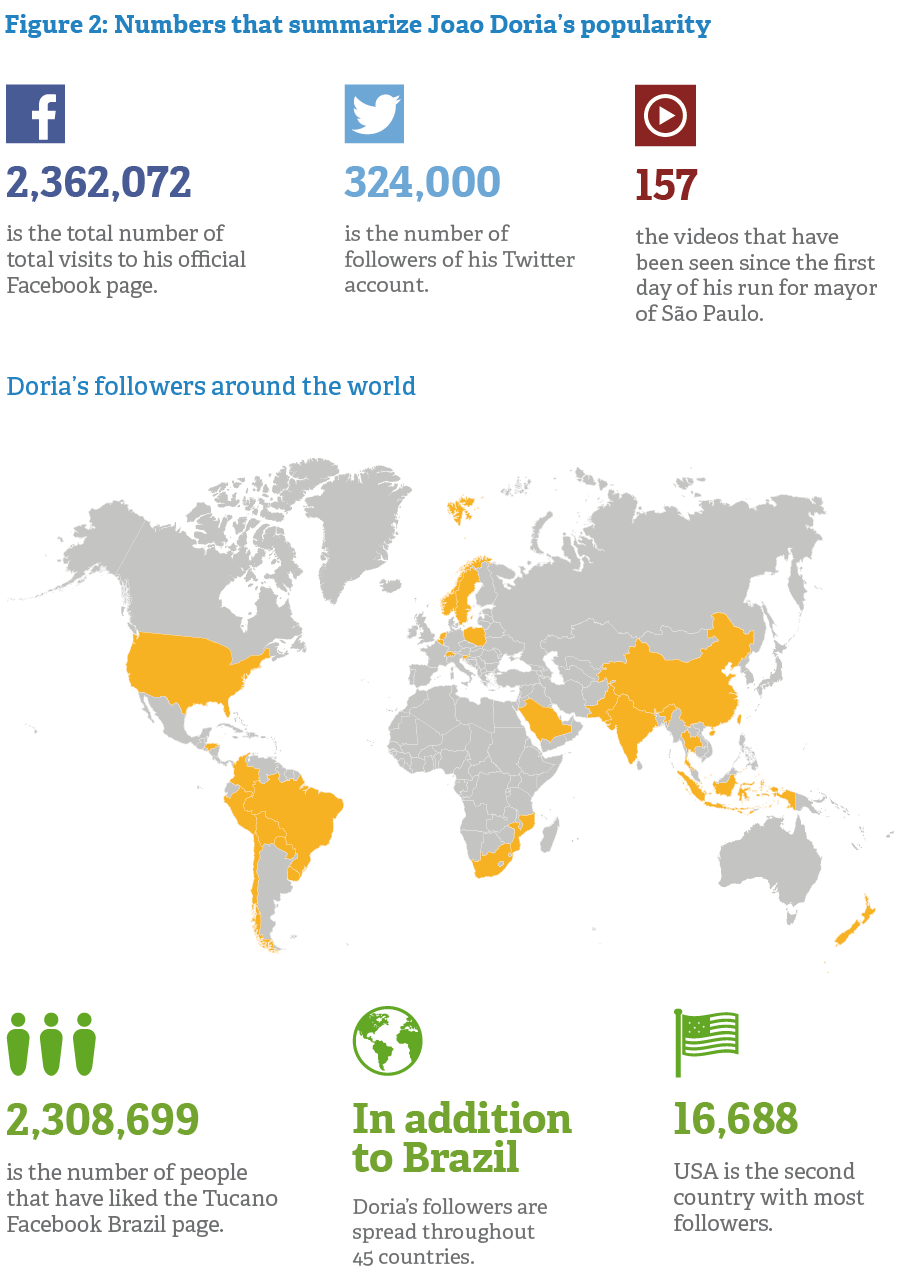

After his first 100 days in office, the mayor now has over two million likes on Facebook and 300,000+ followers on Twitter. Doria has opted for a strategy based of direct dialogue with citizens, via social media, using text, photos and videos.

In its first three months in office, he has published more than 145 videos on Facebook. His post about his visit to McDonald’s (as part of the aforementioned project) has already been viewed over six million times. Not bad for a…mayor?

This strategy of 2.0 channels, which prioritizes videos of Doria staring at the camera and “conversing” with the public, has been key in making his narrative go viral.

According to a study commissioned by Exame magazine, 55 percent of the people of São Paulo recognize that Doria is a mayor who is closer to the citizens than his predecessors.

At the beginning of the election, Doria’s profile was that of a successful, elite and wealthy entrepreneur, far removed from ordinary citizens and the needs of the city. A good narrative and a strong social media strategy have helped reverse that image.

Some specialists also single out the fact that Doria has kept his social media accounts personal and posts to his own accounts, not those of the city mayor. He finances the management of his personal accounts from his own pocket, bringing him closer to the public.

Communication, a management tool

A journalist like Doria recognized the role that communication can (and in many cases, must) play in city management, just as it does in any company.

Due to his massive popularity he is now considered an option for the presidential race of 2018, a possibility that Doria has ruled out for the time being.

However, little progress has been made on his structural agenda of 118 pledges made at the beginning of his term. Despite his positive image, the percentage of people who think he is a bad mayor jumped from 13 percent to 20 percent in his first three months in office.

Just like in a company, good communication does not necessarily mean that management results are positive.

Communication should not be interpreted as an exercise in propaganda or the sale of a product (whether good or bad), but rather as a management tool which, when properly leveraged, opens channels of dialogue with society and conveys a narrative that brings city leaders closer to citizens.

Well-implemented communication helps build the needed trust and transparency between those who govern and those who are governed, hepling identify those spaces of conversation where people can discuss ideas and projects. Clear, consistent and well-structured communication is a key management tool.

Ultimately, communication is what helps build and convey the basic storytelling for a manager. The results of any Government at the end of its term are those that ultimately define whether the created narrative is a believable story with a happy ending or a just another weekend blockbuster.

For now, the way in which the mayor of São Paulo is managing his communication and his reputation is something that is worth following closely, very closely.

Juan Carlos Gozzer is Managing Director at S/A LLORENTE & CUENCA. Expert in reputation management and communication strategies, Gozzer has collaborated in the development of strategic communication plans for clients such as Sonae Sierra Brasil, Cisneros, and Light Energia, among others. With academic education in Brazil and abroad, Gozzer has a Bachelor’s degree in Political Sciences and a major in International Information from the Complutense University of Madrid, as well as a Master’s degree in International Relations from the University of Bologna.

Thyago Mathias is Director at S/A LLORENTE & CUENCA. He graduated in Journalism from the Pontifical Catholic University in Rio de Janeiro and in Law from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. He has 10 years of experience in the largest media groups in Brazil, such as UOL and TV Globo, for which he was correspondent in the Middle East (G1 portal). He majored in International Relations and holds an MBA in Project Management from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation. Thyago has been a communication, reputation strategies and assessment consultor for several public and private institutions.