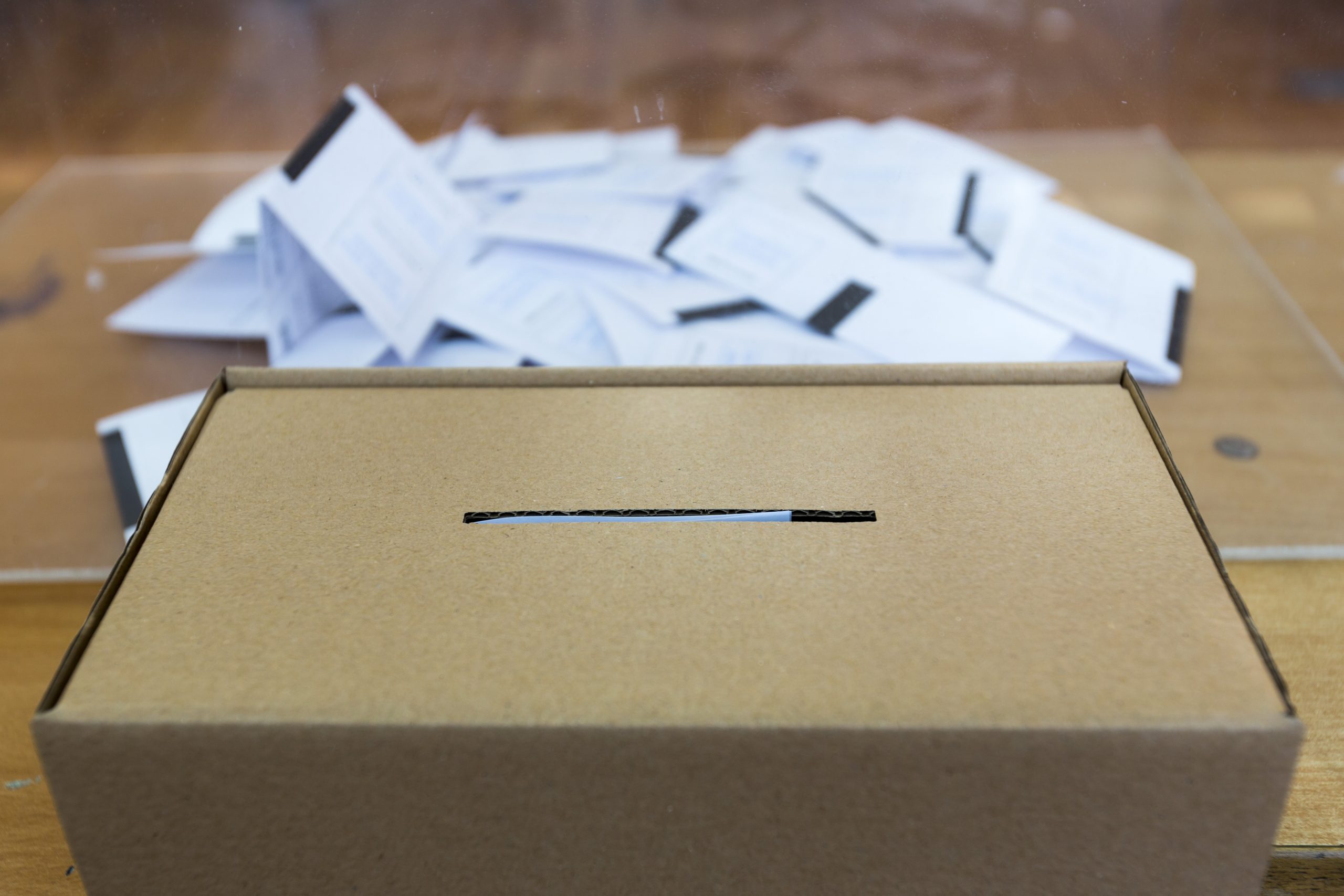

“Nothing about us without us.” It was this motto, used by South African activists fighting for disabled rights, which best captures the essence of the principle behind every grassroots campaign: the right for communities to join together and influence the issues affecting them daily.

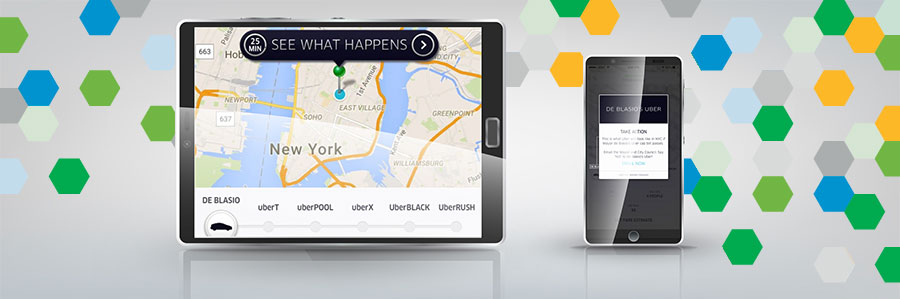

Quoting the old saying “stronger together” seems like such a quick way to explain something complex to anticipate, organize, analyze and quantify. Grassroots campaigns have played an increasingly important role in recent years, seeing the kind of political and media attention usually reserved for more traditional lobbying. Aware of their potential, companies like Uber have capitalized on the collective strength of their users to combine communications, publicity and lobbying. In 2016, someone ordering an Uber in New York could also send a request to regulate the company’s services through “De Blasio’s Uber” directly to the city’s mayor.

Grassroots organizers create the right conditions for citizens interested in advocating for a project to access the tools to meet, join, organize and influence decision-making. These campaigns, frequently used in the Anglo-Saxon world, are now on the rise for political campaigns and NGOs. It is helpful, therefore, to understand how these campaigns are created to identify when a grassroots campaign can be used in our favor to increase the visibility of a project’s social license.

How to inspire people to action

Although social movements are nothing new, the theory behind grassroots organizing started, like so many other practices related to influence management, in the United States, with two researchers from Harvard University: Marshall Ganz and Ruth Wageman. They observed how volunteer programs were organized top-down and by individual objective, with no room for interaction, initiative or leadership. Volunteers would leave organizations because of this solitary and demotivating process, frustrated by a lack of major successes and not feeling involved in the project. The model developed by Ganz and Wageman suggests team members create relationships, take on leadership roles and be inspired by and leverage outside experiences as a motivating and driving force for change.

“It is about inspiring people until action is taken”

The 2008 Obama campaign experimented with the Ganz-Wageman system during the primaries in Iowa and South Carolina, organizing, empowering and mobilizing Obama’s supporters through common goals. He won in both states, while he lost in states like New Hampshire, where he ran a more traditional marketing campaign.

During its second term, he promoted Organizing for Action as a tool to promote Grassroots campaigns that reinforced his legislative priorities.

If we combine the phases of a grassroots campaign with community motivation, it becomes clear that the goal of a campaign is to move citizens away from lack of knowledge and organization toward the satisfaction of a victory, no matter how small. It is about inspiring people to act.

PHASES OF A GRASSROOTS CAMPAIGN

PLANNING

In this phase, communities are unorganized, divided and lack the tools to act.

It is the way a campaign is explained—including how it can be won—that engages people in the process. For this reason, thorough knowledge of the communities is necessary, as it is key to understand what motivates them.

RECRUITMENT

It is at this stage that our campaign initiative reaches the community and begins to generate interest, using messages with a strong emotional component and activities that foster interaction between communities.

ORGANIZATION

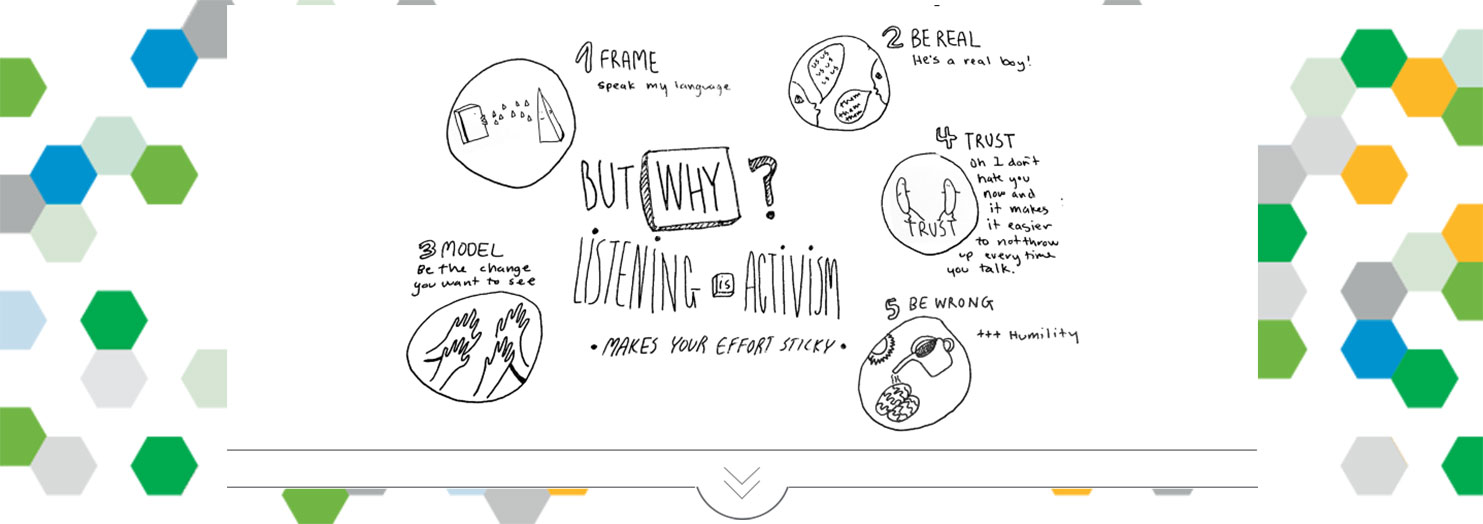

At this stage, the unorganized starts to become organized. Frequent communication with the community to find out what they think and listening to what they have to say, then acting on that information, is essential. Teamwork systems are established, training opportunities offered and work conceptualized as part of the development of a community, rather than as a traditional list of associates and volunteers.

TAKE ACTION

This is when action is taken, as communities now have tools, training, an understanding of the objective and the ability to work independently, as leaders.

CELEBRATION AND EVALUATION

The celebratory stage, even for small victories, is necessary to help communities feel involved in the project and satisfied with its results, generating positivity that can be fed back into the community.

Grassroots as lobbying

There is a growing number of active political stakeholders, influencers and interest groups. Since many have access to decision-makers, the media and networks, it comes as no surprise that messages are diluted, lost and forgotten. Consequently, the mobilization of third parties is a common practice in lobbying to increase a project’s representation and legitimacy, bringing certain issues to the forefront of the political and media agenda.

Traditionally, alliances have been developed through industrial associations between corporate or institutional members who have not managed to mobilize their supporters or, if they have, have done so under a unidirectional communications system in which they work via stagnant and hierarchical groups.

Grassroots campaigns are also a form of third-party mobilization, but are based on an open organizational model in which activists assume responsibility, information is shared and absolute control is relinquished in exchange for collaboration.

“The goal of a grassroots campaign should be concise, clear, shared by all members and measurable in the long run”

Leadership means creating the right conditions so communities interested in advocating for a project have the tools to meet, unite, organize and act. Once such conditions are met, leadership is shared with the activists, fostering the collective power of community members to bring about progressive change.

The goal of a grassroots campaign should be concise, clear, shared by all members and measurable in the long run. We cannot approach it as a temporary initiative, because it implies a deep social change with a strong motivational component.

The Irish Wind Energy Association (IWEA), Wind Energy, developed a campaign to drive energy use provided by the readily-available wind in a country that, despite its many natural resources, imports over 85 percent of its energy.

Just like in any traditional campaign, they built rational messages based on the employment, safety and eco-friendliness of this type of energy, but it only achieved virality through a highly emotional video:

It was Roosevelt who would end meetings by saying “You have convinced me. Now go out and make me do it.” It is true social mobilization can raise certain issues in the political and media agenda, but its technical and social implications mean that we must be aware of when a grassroots campaign fits into an influence management project and when it does not.

It is all about developing projects that place their trust in the collective power of community members to use their life experiences, wisdom, competence and judgment to bring about a progressive change.

Joan Navarro is Partner and Vice-President of the Public Affairs Area at LLORENTE & CUENCA. Graduate in Sociology by the UNED and the General Management Program (Programa de Dirección General, PDG) by the IESE-University of Navarra. Expert in political communication and public affairs, from 2004 to 2007 Director of the Cabinet of the Minister of Public Administration, and in 2010 recognized as one of the 100 most influential people by the magazine El País Semanal. He is founder of the forum +Democracia, entity that promotes institutional changes for the improvement of democratic functioning. He is a member of the Spanish chapter of the Strategic and Competitive Intelligence Professional (SCIP) and contributor to the newspaper El País.

Laura Martínez, is Senior Consultant of the Public Affairs Area at LLORENTE & CUENCA. Graduate in Publicity and Public Relations by the University of Valladolid and with a Master in Management of Institutional Communication and Public Opinion by the URJC. She joined LLORENTE & CUENCA in 2010, since then has worked in the design and development of institutional relations and influence management programs for clients such as the Asociación de Empresas Tabacaleras, UTECA, Cellnex Telecom or Coca-Cola, and corporate reputation projects for UBS or Heineken Spain. She has also worked for audiovisual multinationals such as Discovery Communications and Bertelsmann.