With this year marking the 50th anniversary of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, we remember how the magical realism literary movement morphed the cultural landscape of Latin America for several decades in the 20th century, bringing with it the aesthetic concept of seeing the strange, magical and surreal in something mundane, rational and common.

Has Latin America changed all that much? Despite the efforts of Garcia Marquez and other members of this movement, the yellow butterflies and flight of the beautiful Fernanda have less and less to do with the reality facing Latin America. Unusual and extraordinary terms like “hyperinflation,” “banking crisis” and “debt default” have brought about an economic reality that is much better defined by terms such as “monetary responsibility,” “fiscal consolidation,” “public spending review” and “maintenance of inflation objectives.” We are facing a Latin America that is no longer special or “magical,” that has lost its uniqueness and faces the same, humdrum problems as any other region in any other part of the world: moderate growth, debt containment and fiscal policy implementation. The only exceptions are Venezuela and Cuba, which confirm the tendency to search for balance and trend toward normality.

“Has Latin America changed all that much?”

Looking at the International Monetary Fund figures for the region, growth forecasts are in and around 1.5 percent for 2017, with a spike in demand in key countries supported by the recovery in raw materials prices and relatively favorable financial conditions. Do not be fooled, dear reader—this is not the macroeconomic profile of a Scandinavian country, of a Singapore or Switzerland. We are still talking about Latin America.

If rationality has imposed itself on the economic level, on the political level we also find important changes: in Peru, it is the first time in the last 100 years that four successive governments have changed power in an orderly way, through electoral processes and democratic procedures. Political parties alternate without the incumbent shuffling the deck and, after an opportune constitutional change, can stay in power for many years. The Kirchners or the Correas pass on their positions to the opposition or allies but, in any case, they take a step back, or to the side, so that others assume the reins and lead the destiny of their country.

Is it too civilized? Absolutely. This is what is demanded, in some cases vehemently so, by a new social group, hitherto unknown in the region and which has proved itself as the great architect of the transformation: the middle class. According to data from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), over 60 percent of the population of Latin America—a new record—can be considered to belong to this social group, which allows us to confirm, without exaggerating, that the region is moving in the direction of a “society of middle classes.”

There is no magical effect surrounding this point, but an effective and solid social improvement that, without doubt, has outpaced macroeconomics: the implementation of effective and intense public policies aimed at social spending, health, education, etc. has allowed for a considerable reduction in poverty and deprivation, as well as improvements in employment creation and unprecedented educational opportunities. In its Social Panorama of Latin America 2016 report, ECLAC (the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) pointed out that social spending in the region reached a historical maximum of 10.5 percent of GDP on average in 2015.

However, it is one of the most unequal regions in the world, with a GINI index of 0.46—which is considered high. Here, these social efforts will only have results if applied in a systematic and continuous way, feeding off a middle class that seeks stability, security, growth and improvement.

So if, on the one hand, nobody in the region expects a commodities super cycle to save them and put their growth at 7 percent per year, nor, on the other hand, does anyone fear hyperinflation is going to put the pricing policy in danger, what truly does concern Latin America?

THE NEW-OLD PROBLEMS

There is an old Caribbean saying that says, “When you have beans on your plate, you worry about the television.” It is an apt concept that highlights how, once basic needs are covered, people begin to worry about other aspects of their environment and community.

In this sense, one of the first consequences of the emergence of the middle class, where economic focus gives way to other needs, is that what was traditionally a more local issue has become one of the major underlying problems in Latin America: trust.

Curiously, there would appear to be a very broad consensus on the matter; We are talking about a lack of trust permeating all levels of authority. In Latin America, there is mistrust in institutions, political parties, government, companies and even people. Latinobarometro data are categorical in this respect: no power escapes the suspicions of the citizens, with 70 percent or more expressing little or no trust in governments or political parties holding executive power, in legislative chambers or even the judicial system, which no more than three-quarters of the population trusts. The last bastion with a certain level of trust—companies and business organizations—has seen mistrust among the population rise dangerously close to 60 percent.

This context of dissatisfaction with, on the one hand, democratic institutions and, on the other, with the people running them, is the perfect recipe for another facet of viveza criolla or “native cunning,” to reach genuinely troubling levels; We refer, of course, to the scourge of corruption across Latin America.

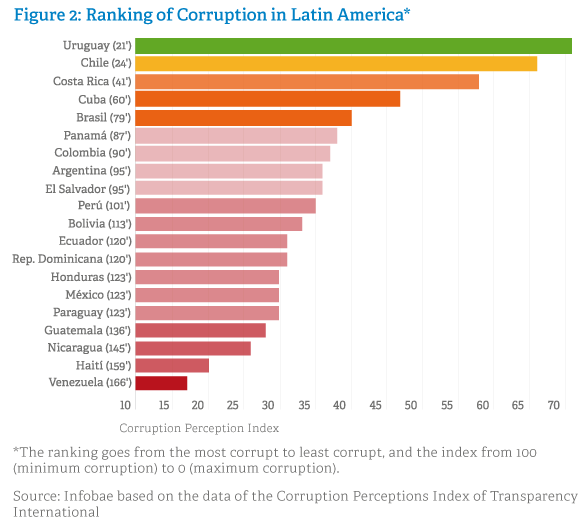

In accordance with the Corruption Perceptions Index, measured by Transparency International every year, we can see that the several Latin American countries suffer from negative perceptions surrounding the levels of corruption in the public sector, although, given the heterogeneity of the region, one cannot generalize or simplify to any great degree.

However, there have been two recent situations that have radically transformed the perception of corruption in Latin America: Firstly, according to Real Instituto Elcano analyses, the issue of corruption now occupies an important place in the public agenda for many countries, beginning with Brazil, Guatemala, Chile, Honduras, etc., which have seen corruption debated in parliament, criticized among the population and, of course, become the target of the media. This rejection of illegal enrichment has gone from something that rankled on an individual level to a major issue in the public sphere, leading to mass street demonstrations and a rejection of the impunity traditionally afforded to this type of behavior.

On the other hand, major cases of business corruption, some even taking place on a regional level, have seen a qualitative change in the analysis of this phenomenon: the privatization of corruption. The focus is more general; Public officials are no longer the only offenders, and fingers are now being pointed at corrupt companies, even though they were there all along.

“In Latin America there is mistrust in institutions, in political parties, in the government, in companies and even mistrust in people.”

Along with the loss of trust and rising corruption, the third element we must highlight in this map of new-old Latin American problems concerns compliance with the law. In Latin America, if there is an abundance of one thing, it is rules. Public policy is designed systematically across all areas of state intervention—rules and regulations, in some cases at the cutting edge of regulatory invention, broadly cover all areas in which citizens need governance.

So, where is the problem? It is simply that they are not obeyed. In the majority of countries, public policies are well planned and better designed, but there comes a moment of weakness in their lack of implementation and fulfillment.

For Professor Garcia Villegas, from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, breaking the rules is not always an exceptional act in Latin America; On the contrary, it may become—as is the case with traffic violations, street trading and, worse still, tax regulations—the norm, establishing themselves on the margins of the laws in force, bringing about a change in the law itself or just supporting indefinite nonenforcement, making it obsolete.

In this regard, those that do not obey laws do not receive resounding social rejection, and their behavior, rather than being deviant, is considered the norm. To a certain extent, it is regulated in the societies in which they live. In general, both they and society do not perceive this flouting of the laws as a disturbance to public order, much less a criminal act.

But we should be conscience of the implications this has: taking the example of tax regulations, noncompliance is so deep-rooted in society that disobedient behavior can become socially tolerated, if not accepted. Sometimes, in cases of noncompliance by politicians, it is even electorally rewarded. Nobody doubts how difficult it is to collect taxes in Latin America.

CONSEQUENCE OF THE NEW-OLD PROBLEMS

The fact that the Latin American society has shifted from strictly economic concerns to others, such as lack of trust, corruption and legal noncompliance, moving toward a more social focus based on perceptions, has also led to changes in citizen behavior. Again, we must emphasize that these problems are not new and we are not surprised by their existence. The truly new development is that they now form part of the public agenda and are here to stay, occupying space in their own right.

According to the IDB Research Department, Latin American citizens firmly support democracy but they are dissatisfied, as we have seen, with the institutions representing them and the results of public policies. This lack of trust and doubt as to whether the laws, although good, will ever be applied—all in the context of never-ending corruption—leads Latin American citizens to tolerate certain public policies that, institutionally speaking, shoot themselves in the foot.

“It is the idea of a relatively close personal benefit compared with a relatively distant group benefit and that there is no trust.”

The distrust of the future causes a preference for policies with short-term benefits, though their long-term costs may be very high. By way of example, the concept of a “retirement pension” is not very well established due to underestimation of future needs and a preference for short-term planning. According to IDB data, only 17 percent of the Latin American population will receive a pension. Likewise, the policies with visible and tangible effects are preferred above those that are more qualitative or rely on long-term effects.

In this new context, other more socially accepted policies involve transfers or subsidies rather than the improvement of public resources. This is because it represents relatively close personal benefit compared to a relatively distant group benefit, and there is no trust.

“IT IS THEIR CULTURE, DUMMY!”

In all of these new concerns, there seems to be a common element—one of nature, not the economy, that belongs to another level of analysis: culture.

Economists have done their jobs and passed the tests of stabilizing the economy and building foundations to allow sustainable growth. But now, what is truly challenging is the construction of a solid civil base, creating a populace that takes on the culture of rights and duties, of self-criticism and self-regulation. A populace that protests when others disobey. A culture of obeying rules—a culture of legality—is essential to achieving an integrated coexistence marked by solidarity and that, without a doubt, favors productivity.

The structural element, the DNA of these new concerns, has a deep-rooted cultural component that builds social behavior in its own image, in accordance with the perceptions citizens develop in the places they live and work in and in relation to the communities they interact with.

Seeking the simplest definition, culture is the set of beliefs that governs people’s behavior. When we talk about culture, we are referring to three concepts: beliefs, attitudes and behavior. Beliefs allow for citizens’ attitudes to be shaped against the backdrop of social reality, and these attitudes display themselves as behavior.

According to Antonio Diaz, director of The Last Mile, “Every culture influences behavior by means of more or less explicit punishments and rewards. But this coercion only works while the reward or punishment prevails and as long as there is no a greater prize or punishment in another direction.”

If citizens believe they will also benefit by paying taxes and contributing to society, their attitudes will be completely compliant with fiscal rules; positive attitudes toward following these rules result in citizens paying their appropriate taxes… but, what happens if the belief is that there are no personal benefits to paying taxes? If there is a negative attitude to tax regulation? If the attitude is, in essence, “let someone else pay”?

Then, there is no need to change the rules, or make them more coercive, or add new regulations or improved economic projections. The culture itself needs to change.

TO CHANGE THE CULTURE, IT IS TIME FOR THE COMMUNICATORS

Jose Juan Ruiz, chief economist and manager of the IDB Research Department, was very explicit at a recent conference in Madrid: “Culture is the only institution that does not come with an instruction manual of how to change it.”

Is it so difficult to bring about cultural change? Without a doubt, since it impacts our values, beliefs, attitudes and behavior. The problem stems from the fact that all these elements are found at the foundation of society, which generates its own protective barrier so things stay as they are. Beliefs are built on the basis of intangible perceptions, leading to the convictions that influence citizens’ attitudes.

If we talk about the perception analysis and management, their capacity to create conviction and influence, are we not talking about the tools and territories that form a communicator’s domain?

“Culture is the only institution that does not come with an instruction manual of how to change it.”

Culture can be changed. To do so, the beliefs that generate old attitudes must be broken down, provoking a change in behavior: it should not still be acceptable for people to trade on the streets, to not have license plates on their cars and to not pay their taxes. The new belief will be that the key benefactor of fulfilling your obligations to society is the you yourself, and thus, the rest of society.

Nobody is saying this is easy, but it is without a doubt possible by designing a Strategic Plan for Change, with defined beliefs to modify and communities with mistaken perceptions to target. These will be the first steps in this arduous task. From there, a new narrative will be created, helping citizens understand how they are the main beneficiaries of this new behavior.

The next phase is to find “agents for change” who will foster this difficult process. In particular, communication will serve as a structural element around the parties involved, allowing for active dialogue among the relevant audiences involved in this transformation.

The challenge lies in instilling trust among Latin American citizens. To do this, it is essential for governments and all types of institutions to fully commit to lead an authentic “coalition for change,” planning, coordinating, resourcing and later, monitoring and mediating.

It is time to face up to this new challenge in Latin American society. With economic foundations being consolidated that allow for sustainable economic and social development, accompanied by their logical and expected ups and downs, it is time to change the culture as well. And we, as communicators, are ready.

Claudio Vallejo, is the Senior Director of Latam Desk at LLORENTE & CUENCA, Spain. He holds a degree in Law and Diploma in Advanced Studies in Communication (DEA) from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, specializing in international relations and international marketing by the University of Kent at Canterbury, UK. He has previously served as Senior Advisor to the multinational strategic communications and public affairs firm, KREAB. As Communications Director he has performed his duties in several relevant companies in each of its sectors such as CODERE, ENCE, SOLUZIONA and Responsible of International Communication of the electrical UNION FENOSA. Prior to this business experience, Claudio was a Commercial Attache in the Commercial Office of the Spanish Embassy in Quito, Ecuador.